In today’s modern industrial operations, few processes rank higher in terms of importance than compressed air and no process places a higher demand on energy consumption. As a key utility, its uses include running machinery, conveyance in handling systems and switching for instrumentation and electrical systems to name just a few. However, energy demand is negatively impacted when poor maintenance practices allow inefficiencies to spiral out of control and the single biggest culprit is system leaks.

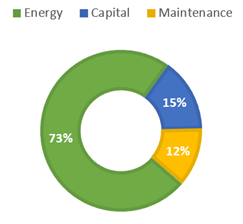

Look at this simple breakdown of a typical investment a company would need to make for a simple compressed air system. The chart reveals that energy accounts for as much as 75% of the total system cost.

It’s a surprising statistic as conventional logic would have us believe that up front capital and ongoing maintenance costs should dominate. True, capital costs for compressors and delivery systems are significant, but not ongoing. If a system is specified correctly and maintained well over time, its capital costs can be depreciated. A poorly maintained and leaking system will never fulfill demand, continually drain resources and have a negative impact on energy. An inefficient energy wasting system further hurts our environment through additional and unnecessary greenhouse gas emissions.

The fact that we don’t always think of compressed air in terms of energy consumption explains why so little attention is given to finding and fixing leaks. Leaks are expensive. According to the US Department of Energy, average systems waste between 25 and 35% of its air to leaks alone. In a 1 000 SCFM system, 30% leakage translates to 300 SCFM. Eliminating that leak is the equivalent of saving more than $45 000 annually (depending on where your plant is located and that region’s energy costs, the amount saved can be three to four times higher).

A better understanding of leak complacency is needed if we are to get to the core of the problem. Why do we pay more attention to energy efficiency lighting (agreed, there are gains to be had with good lighting and efficient uses) and continue to ignore inefficient compressed air systems? One explanation is that compressed air leaks are not seen. I grew up listening to my parents say, “don’t leave the lights on” so efficient lighting was ingrained at an early age for me. They never said much about leaks. Yet, I can still recall leaking airlines in my father’s workshop.

In the factory setting, a steam leak is obvious and an oil leak even more so. However, air leaks don’t create a visible plume nor do they make a dangerous and slippery mess on the floor. They don’t have an unpleasant odor and mostly, we ignore or can’t hear their continual hissing.

So, is it truly a case of “out of sight, out of mind”? Is energy waste and system inefficiency still a low priority for manufacturers? Could it be that compressed air is a background process taken for granted? Consider your compressed air system and all the areas where pneumatics are employed at your facility. Expand your thinking beyond the factory walls where compressed air makes possible many things in science, technology and everyday living. From jackhammers for road repairs to drills in the dentist’s chair, from the tires that roll us to and from work, school and play, to our children’s inflated soccer and basketballs, compressed air is all around us… and yes, taken for granted.

A culture change is occurring in industry where it’s needed most. Industry represents the biggest consumer and, therefore, largest potential gain. It is a dual challenge and a dual opportunity. The challenge is to invest in more efficient energy and environmentally conscious practices. The opportunity is to improve profitability and slow the effects of global warming. We have an insatiable thirst for electricity and the fossil fuels necessary to quench our thirst are being used up at rates we cannot afford. Two side effects concerning everybody are the diminished supply of non-renewable fuel sources and the effect that increased levels of CO2 have on global climate change. Diminished supply means continued higher energy costs, while global climate change represents something much more expensive.

Not all companies are sitting idly by waiting for others to take action. Many have already begun programs that address energy efficiency and specifically target the compressed air system. AFG Glass is the second largest flat glass manufacturer in North America and the largest supplier to the construction and specialty glass market. Founded in 1978, AFG is headquartered in Kingsport, Tennessee. With its three divisions, it is a fully integrated supplier. One division is responsible for flat glass manufacturing, another for advanced energy efficient coatings and a third fabrication division that adds value to their finished product through tempering, laminating and insulating. In total, AFG has nine glass production operations, 34 fabrication/distribution centers, 4 sputter coating lines, 5 insulating plants and one laminating facility. They have more than 4 800 employees working in their North American operations.

AFG has implemented airborne ultrasound programs in some of its manufacturing divisions. Mainly, ultrasound was considered for its reputation as an overall predictive maintenance and trouble-shooting tool. When several technicians attended the Level 1 Ultrasound Certification Training, they learned the technology they invested in would be used for much more than trouble-shooting.

Ultrasonic Leak detectors work like simple microphones that are sensitive to high frequency sounds ranging beyond the human ear. They enable us to hear problems with machinery on the factory floor, regardless of background noise. Ultrasound detectors can be simple leak detectors or advanced data collectors capable of trending and diagnosing machine failures and plant inefficiencies.

A typical compressed air system can be surveyed for leaks in one or two days. Larger plants may take longer, but the benefits to finding and fixing leaks are well worth the investment in time.

Douglas Bowker is the Plant Maintenance Superintendent at AFG Industries Greenland,

TN plant. He has been instrumental in the implementation of ultrasound testing to improve the well-being of their plant’s equipment.

“Compressed air is not free,” writes Mr. Bowker. “It costs Greenland approximately $137 000 per year to supply compressed air to the plant. Air leaks therefore cost us money. A small leak that is undetected by the human ear can typically contribute to $3 000 of cost per year. The Ultrasonic equipment can now be utilized in a cost saving manner to detect such leaks and fix them proactively.”